TWENTY-SEVEN

Ettore Majorana™

In 1966 Edoardo Amaldi wrote The Life and Work of Ettore Majorana. In 1974 director Leandro Castellani shot a film on Ettore and published Dossier Majorana. In 1975 Leonardo Sciascia wrote his classic La Scomparsa di Majorana. Ettore’s letters and documents were published by Erasmo Recami in 1987. Since then, Italian books on Ettore have sprouted by the dozen. If you add the hundreds of newspaper articles putting forward conspiracy theories, plus TV documentaries, comics, and novels, Ettore can hardly be said to lack an afterlife. The search for neutrinoless double beta decay can only envy such a level of attention.

Many have tried writing about Ettore in fiction format. It has always been disastrous: In a fictional world the temptation to invent answers is just too great. In trying to speculate beyond the facts, Ettore always becomes a Mickey Mouse character. In L’inglesina in Soffitta he inexpertly has sex with a Scottish spy girl (in Italian novels British women are invariably portrayed as the ultimate tarts, which is, of course, unfair.) In a French book he runs away to Argentina where he becomes a family man; one of his daughters is named after Maria.

Then there are the “real-life” stories purporting to solve Ettore’s mystery. A prime example: Signorina Tebalducci, a Florence lady who claimed in the Italian press to have dated him. According to her, it was not a happy affair even by the standards of the day (when vaginal penetration had to be preceded by a blessing at the altar). Ettore didn’t speak much, and whenever things became interesting in the slightest, a group of “foreign-looking men” would turn up, take him aside and talk for hours, completely ignoring her. After discussing the matter with a brother in the Carabinieri, the signorina concluded that she was being used as a “schermo,” a statement that underlies the theories portraying Ettore as a spy, kidnapped by the enemy in 1938.72

The mathematically oriented clochard who once lived in Mazara del Vallo.

Ettore’s brother Luciano vigorously dismissed this story, stressing that Ettore had never been to Florence. But Signorina Tebalducci performed a remarkable public utility service. She filled in the gap that other accounts of Ettore leave wide open: his private life. A lie is certainly less infuriating than a void.

Personally, I like to collect Majorana conspiracies the way others collect stamps: There are nearly as many. My favorite concerns “l’omu cani,” Sicilian for “man-dog.” In 1940 a drifter appeared in Mazara del Vallo, in southern Sicily, not far from the setting of the detective Montalbano stories. The self-named Tommaso Lípari claimed to come from Africa and carried with him a profusion of bags. He never begged and didn’t accept money, slept in a cave at a nearby ruined castle, and kept his distance from everyone. He chain-smoked, crafting his cigarettes from butts he picked up from the ground. And he could do cubic roots in his head.

One morning in 1973 the man-dog appeared dead. “Natural causes” was entered in the official report. To everyone’s surprise his funeral attracted “notorious VIPs” (excuse the euphemism). It further transpired that Signore Lípari had a deep scar on his right hand (not necessarily associated with crashing a vehicle) and wore a bracelet with Ettore’s birthdate engraved on it. But what set imaginations alight was that the case attracted the attention of anti-Mafia hero Paolo Borsellino.

Borsellino was born and raised in the Palermo district of La Kalsa, where they tell tourists not to go, and had been a childhood friend of that other anti-Mafia hero Giovanne Falcone. Aware of their surroundings, they put themselves through law school, so that one day they could cripple the Mafia. The results are well-known: They now have an airport named after them. Both died from car bombs. The blast hitting Falcone opened a ten-meter-deep crater, and the highway had to be redesigned. You can’t run away from death, but you can be prepared for it. Falcone and his wife decided not to have children because they didn’t want to leave orphans.

Borsellino concluded in his report that Signore Lipari was not Ettore Majorana. Unwittingly he cast the Mafia aspersion on both.

Whoever the man-dog was, people missed him when he died. In Mazara del Vallo he’s still invoked by adults to frighten misbehaving children. If someone goes mad people say that “he’s become worse than the man-dog.” And if you need a cubic root evaluated, things have never been the same.

This is only one of the theories in my collection, and to be honest most strike me as disingenuous: nothing like a good conspiracy to attract attention. There are exceptions, of course; sometimes they’re just so alluring. I can’t forget the conversations I had with my friend Professor Francesco Guerra who, having spent hours scorning Ettore theories, couldn’t resist telling me his own.

He found a letter from Florence physicist Gilberto Bernardini to Ettore’s friend Giovanni Gentile Jr. The letter is not dated, but practical details included place it around May 1938 (it refers to a trip Gentile would take to Germany in June 1938). It’s a reply to an earlier letter from Gentile (presumably reporting on the events of March) and opens with “As you can imagine, the news about Majorana has filled me with great joy. It’s not a pretty thing, perhaps, but it’s not as tragic as we had imagined. We can all be happy about it.”

If this letter was indeed penned in May 1938, how can we interpret it? No two ways about it. Obviously Ettore didn’t commit suicide (not as tragic as they had imagined). He did something not very “pretty” (ran away from his family and responsibilities), but it could have been significantly worse (i.e., suicide). They’re all well aware of his fate, and can be “happy about it,” even filled with joy.

Unfortunately it’s not so obvious. The dating is soft. The letter could also have been written at the end of 1937 (the practical details referred to can be accounted for in other ways). In which case the letter simply refers to the mundane shenanigans of the concorso (not very pretty to suspend it, but they all got accommodated in the end). But one can’t suppress a glistening in the eye. This letter embodies the lingering sensation that friends and family know what happened but aren’t telling. My sincere congratulations to them.

But these somewhat measured conspiracy theories pale in comparison to the all-out flights of lunacy. That Ettore’s family is cursed; that aliens have abducted him; that he ran away to the center of the Earth via Etna, where he’s working for the benefit of humankind. Shall we ratchet it up a notch in abject insanity? If so, let’s indulge in an Internet myth I’ve added to my collection: the “curse of the Majoranas.”

During recent restoration works in the Steri (the ancient Palermo headquarters of the Inquisition) a variety of graffiti emerged from beneath four centuries of plaster, left by inmates due to be tortured and killed. Some of them were signed by Paolo Majorana, who was there in 1681. Understandably, his graffiti contain nothing but gritty curses.

In a certain town in the middle of Amazonia political and economic life is controlled by the Majoranas. The family patriarch has been nicknamed Majorana, O Mafioso, and many people who’ve been aggrieved by his prepotencies have admitted that they’re too scared to take their cases to the police. Instead they’ve resorted to good old-style Brazilian voodoo.

On November 12, 2003, a group of Italian Carabinieri were killed by a suicide bomber in Nassiriya, Iraq.73 Among the fallen heroes was Orazio Majorana. The premature death of Orazio affected the family enormously, but no one more so than his brother, as chance would have it, named Ettore. Ettore Majorana became a vocal pro-peace activist, denouncing the hypocrisy of Western intervention, and demanding the recall of all Italian forces. But after a flurry of political activity, young Ettore buckled to depression, never quite getting over his bereavement. A few months later, the twenty-two-year-old modern Ettore Majorana appeared drowned. Close friends believed it was suicide, but no one really knows. This creates a bizarre parallel between the two Ettores: one left apparent suicide notes but no corpse; the other a corpse but no suicide notes.

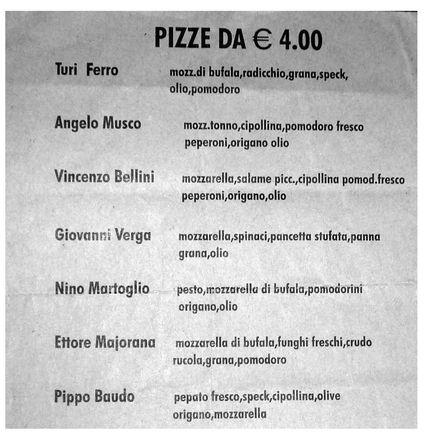

Pizza Ettore Majorana: Buffalo mozzarella, fresh mushrooms, Parma ham, rocket, “grana” cheese, and tomato.

The fact that none of these three Majoranas is related to our Ettore hasn’t stopped abundant Internet literature from uniting them under the “curse of the nuclear physicist,” the “curse of the Majoranas,” and their evident relation to the “curse” of a certain combustible baby. Perhaps in this context it’s not so odd that a scientific article appeared on the WEB archives stating that Ettore had placed himself in a quantum superposition of dead and alive, like Schrödinger’s cat. And that another article associated his name with a neutrino device capable of deactivating all the nuclear weapons on Earth.

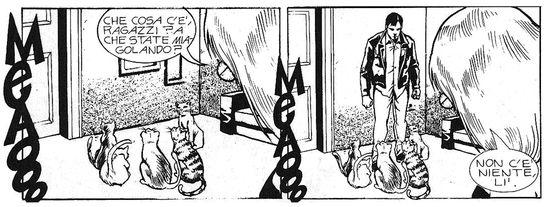

But then, by now Ettore has become a trademark. He has a pizza named after him. He’s a hero in comics, surrounded by cats in the fifth dimension. People manage to keep a straight face while arguing over who owns the copyright to his suicide notes. Ettore has fallen prey to those who insist they have exclusive rights to his soul, those who allege they own the patent for oral sex.

What is it, boys? What are you mewling at?

There’s no one there. . . .

He doesn’t need neutrinoless double beta decay for anything. In the vast seas of the subculture, his afterlife is in full swing.