TWENTY-ONE

The Search Party

What could have happened to Ettore after he met Gilda Senatore? He posted his letter to “Dear Carrelli” and must have written the letter a la famiglia left in his room. He then had plenty of time on his hands until 5:00 pm, when according to the receptionist, he left the Albergo Bologna. It’s a short walk to the port, from where the boat would depart at 10:30 pm. Did he have dinner? How did he fill these fraught hours?

The boat is about to leave and from the upper deck, some ten meters above the water, I appreciate what a drop it is. The water is filthy, awash with garbage and dead fish. Not a nice plunge, but one would likely wait for cleaner seas. The boat whistles noisily and slides away from the pier as I retrace Ettore’s steps almost exactly seventy years on. Tirrenia, the company that took Ettore, is still in business. Admittedly, the trip is now made by a ferry carrying trucks and cars, but I still find it vaguely damning that it takes longer than it did in Ettore’s day.

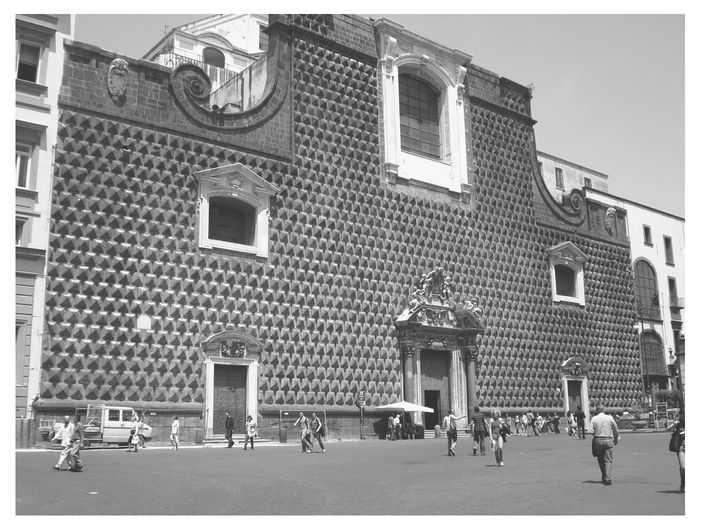

As we leave the harbor, we feast on great views of Vesuvius. How ironic that someone born in the shadow of Etna would leave reality under the quiet watch of another famous volcano. This one isn’t as active as Etna, but is far more dangerous and unpredictable. Ask the people of Pompeii and Herculaneum who died buried by ash in AD 79, when the volcano most famously erupted. Since then, eruptions have been sparse but vicious; for example, in 1631, ash from an eruption fell as far as Istanbul, 1,200 kilometers (about 750 miles) away.

Vesuvius in the distance, as the Tirrenia ferry bound for Palermo departs from the port of Naples.

Fermi was quoted (by Carrelli) as saying, “With [Ettore’s] intelligence, if he decided to disappear—or make his body disappear—he’d have succeeded.” Mussolini’s police chief, Arturo Bocchini, commented in response to Ettore’s vanishing, “Corpses can be found, it’s the living that disappear.” But one of the most far-fetched explanations I’ve heard for the lack of a body is that, having sailed to Palermo and back, Ettore took the train to Vesuvius and threw himself into the crater. As we enter high seas, I note that he could have accomplished the same effect with much less effort. In front of me on the boat is a man-at-sea alarm. A sailor once told me that should someone fall overboard, whoever raises the alarm has to keep pointing at the spot where the person fell in. Otherwise, with no reference points, by the time the boat is turned about, it might as well have gone around the globe.

My mind wanders irrelevantly and mathematically as I consider what a truly two-dimensional setting the sea is. Getting lost on land, in no matter what labyrinth, is always one-dimensional and infinitely simpler. I see a mouse crossing the deck, and as I turn a corner, the full brunt of the sirocco pushes me off balance, making me slide on the wet deck. A puerile thought crosses my mind: Maybe Ettore just fell in by accident. In the distance, I see the lights of other ships. My mind wanders further.

And then I get a glimpse of what could have happened to Ettore on that anguished night, as he embraced his inner troubles. Maybe he didn’t fall in by accident, but life might have intervened. It is known that the boat he took from Palermo was carrying an entire battalion returning from great conquests in West Africa. Imagine the din! In fact, I don’t need to imagine, courtesy of a school trip, the teachers oblivious to their charges running riot and alternating screaming with serial vomiting (it only takes a critical mass of one to start a chain reaction, unlike with uranium).

There was I, trying to summon Ettore’s tortured soul after he left Gilda Senatore, instead finding myself wondering if I should throw a couple of the noisy brats overboard. I might get some peace, and in the bargain test my theory that their bodies would never be found.

In an analogous environment, back in 1938, it would have been quite difficult to commit suicide (unless he jumped ship just to get away from the racket). Maria talks about a decision triggered by circumstance, “At dawn he was seen at the bridge,” she said in Bruno Russo’s documentary. “Dawn, as everyone knows, is the most delicate moment for those considering suicide. I am sure that Ettore threw himself into the sea, taking with him all the weight of his anguish and his atrocious doubts.” But circumstances could equally well have conjured against it.

As the night unrolls, things quieten a bit on the boat, but never completely. I go to the bar and am gifted by serendipity: A TV set is blaring a moronic documentary titled Did Hitler Have the Bomb? Answer: no—after an hour of dim commentary and dramatic music, and just before the presenter is teleported out of the program. A funny coincidence . . . did Heisenberg and Ettore have more in common than we know? Heisenberg was certainly perilously close, at least conceptually, to the bomb, and this only a few years after that day in March 1938.

Back on deck, I realize what a gloomy figure I must cut: pensive and stark, staring at the sea. Maybe the insomniac brigade is worried I might be contemplating suicide. A girl comes out to smoke and waits to be chatted up. I move to the rear. What a sad bastard I must look, refusing to play the game of life, shouting and fucking, throwing up against the wind. I watch the wake for a long time, the cigarette butts flying past me into the night, like fireflies from Mars. In our world of the “normal,” anyone who thinks is likely to appear suicidal. And yet, suicide or not, we will all be there one day, not just Ettore. We are all the same, only in different seasons.

Ettore was seen by Gilda on Friday morning, and then the factoids begin. Factoid number one: He boarded a ship to Palermo and then returned to Naples. This is known for a “fact” because, upon request from the family, Tirrenia located the tickets. Fact? Wrong. Factoid. Tirrenia merely said they recovered his tickets: No one actually saw them. Even today, in the age of computers, you should see the royal mess that pervades their ticket collection.

Then there are his letters. He posted one to Carrelli in Naples and left another in his room. The day after, in Palermo, he wrote a second letter to Carrelli on Albergo Sol letterhead, informing him of his change of heart. He rarely wrote on letterhead, so it looks as if he was trying to make a point. It’s alleged that this letter proves he did arrive in Palermo, but again we are in the realm of factoids. It is his hand writing on a Palermo hotel letterhead, but one could imagine (admittedly forceful) ways in which he could have produced this letter without ever reaching Palermo.

If he was indeed in Palermo, then I can see why he sent a telegram to his Naples hotel stating, “Please keep my room.” They hadn’t seen him for a few days, and apart from the danger of giving his room away, they might have gone in, opened the letter to the family, and raised the alarm.

But on his alleged trip back from Palermo, something very close to fact did occur, at least if you believe Tirrenia’s records. As chance would have it, Ettore shared a cabin with a Palermo University mathematician, Professor Strazzeri. An Englishman, Charles Price, occupied a third cabin berth. The latter was never traced, but the former answered an inquiry from Salvatore (enclosing a photo of Ettore). Professor Strazzeri replied that “it is my absolute belief that if the person who traveled with me was your brother, then he didn’t kill himself, at least not before the arrival in Naples.”

Upon closer inspection this, too, could be a factoid. Professor Strazzeri didn’t talk to Ettore and could not, therefore, be sure that it was him. His account is also confusing; he says that the so-called Charles Price “spoke Italian like us, people from the South, and I assumed he was a shopkeeper or below, in short, someone without the refinement of manners that results from culture. . . .” How to explain this, since Price was English?

One possibility is that Tirrenia was mistaken, and Ettore wasn’t in that cabin. A theoretically more elegant explanation comes from Sciascia, who argued a “third man” scenario. “Since Prof. Strazzeri exchanged few words with the man supposed to be Charles Price and none with the presumed Ettore Majorana,” he wrote, “it’s a reasonable hypothesis that the man who didn’t speak, identified later to Strazzeri as Majorana, was in fact the Englishman; whereas the one he was told was Price was instead a Sicilian, a Southerner, the shopkeeper he appeared to be and who was traveling with Majorana’s ticket.” This explanation implies that Ettore remained in Palermo and gave up his ticket. It’s contorted, but as Sciascia points out, it avoids the conspiracy of turning Price into a Sicilian passing himself off as an Englishman and following Majorana, “whence the myth of the Mafia trafficking in physicists as it traffics in women.”

But there are worse factoids, such as the story of Salvatore and Luciano, already looking for Ettore, being accosted in Palermo by a stranger who told them: “I know who you are and who you’re looking for; the friends of the friends are at your disposal.” I don’t need to translate the euphemism. A few days later, as legend has it, they received a complete report of Ettore’s hour-by-hour moves in Palermo, sadly ending with his departure to Naples. “I am sorry to be unable to do more to help a man who has brought honor to our island,” the stranger reportedly said. When I confronted Fabio with this story (presumably the report would still be with the family), his surprised face said it all.61

Alarm bells started ringing at top volume on Monday when Professor Carrelli sought out Ettore unsuccessfully and sent news to the family. On Tuesday—lecture day for Ettore—he had to tell the students that the course was cancelled. Imagine the gossip this must have sparked, the extravagant explanations the students would have produced. Another of Ettore’s pupils, Nada Minghetti, stated in an interview that when Ettore didn’t turn up on Saturday, they were all delighted. It was a sunny day, and they were most happy to get a day off. It was only on Tuesday that the rumors started to spread, and gradually Nada realized that something serious had happened (I doubt Gilda Senatore ever thought otherwise). It was also on Tuesday that Salvatore arrived in Naples. He went to Ettore’s lodgings at Albergo Bologna. It must have been eerie to enter his room: empty and silent; on the desk a letter “to the family.” The room of a man who has abandoned the world.

Later, Luciano arrived in his car and the search began. Police and family worked independently but interacted. The family never believed Ettore committed suicide; the police, on the contrary, were certain he had. They placed a photograph of Ettore in the La Domenica del Corrieri under the rubric “Chi l’ha Visto,” “Reporting Vanished People.”62 At first, Luciano and Salvatore thought he was still in Palermo, but then the evidence reversed to Naples. In addition to Professor Strazzeri’s account, they received a report from the monks of San Pasquale a Portici near Naples. Then from a nurse who had treated Ettore and saw him between the palace and the gallery, coming from Santa Lucia. And then there was the priest of the church of Gesú Nuovo in Naples who swore he’d seen Ettore in his church in early April, begging to be admitted to a monastery.

All this got on Luciano and Salvatore’s nerves—and thus the “search party” began. They scoured the Campanian countryside searching for Ettore in monasteries and peasant dwellings. These searches continued for over a year, from hamlet to hamlet and monastery to monastery. They didn’t give up until Luciano, obviously distressed, one day ran over a little girl with his car. He was apparently very affected by this accident, and that’s when he realized that enough was enough. The same level of commitment cannot be attributed to the police.

Initially, the police took a casual attitude towards the disappearance, believing it to be a clear-cut case of suicide. But then the relevant strings were pulled, rendering inappropriate their unconcealed lack of interest. Ettore’s friend Giovanni Gentile Jr. implored his powerful father to intervene. Senator Gentile obliged and went straight for the jugular: He contacted Arturo Bocchini. You should perhaps be made aware of what this meant.

The architecturally rather odd Church of Gesú Nuovo in Naples, where Ettore allegedly made an afterlife appearance, requesting “an experiment of religious life.”

All totalitarian states have a special police to “defend the state,” spying on all activities, terrifying everyone, and torturing and killing anyone who fails to be cowed. In practice, this means nothing but legalizing and using the services of the usual psychopaths and other thugs to be found everywhere. Germany had the SS and the Gestapo; Portugal, the PIDE; Italy, the OVRO. Arturo Bocchini was head of the OVRO in 1938. He was the sort of man who could legally have anyone killed if he so wished; who could find out who had farted anywhere in Italy and beyond.

At the behest of Senator Gentile, Bocchini received Salvatore and ordered a dossier on Majorana to be opened. The contents, still on file today, are a masterpiece of deliberate incompetence. Regardless of Senator Gentile’s efforts, clearly Ettore was a low priority for OVRO. For the powerful political police, it was merely a matter of humoring the Majorana family, in deference to Senator Gentile. The facts on file are vague and careless. They ignore claims that Ettore had been kidnapped by foreign powers,63 a matter falling squarely into their remit. Layers of blue, green, and lilac writing color-code, according to hierarchy, the reports documenting the diligences, or lack thereof, of the state police regarding Majorana. They don’t even bother getting the dates right. It’s blatant that no one cared.

A couple of pages from Ettore’s secret police file, remarkable for being so uninformed.

Later, Fermi and Dorina petitioned Mussolini himself. Fermi’s letter opens with “Duce!” the equivalent of “Führer.”64 Dorina’s letter instead addresses the “supreme inspiration of all the Justice.” Hypocritically, she claims that Ettore had “always been balanced and the drama of his soul and nerves is therefore a mystery.” She insists he had no suicidal “clinical or moral precedents.” On the contrary, given his life of study and hard work, she claims that Ettore should be considered a “victim of science.” She notes that Ettore’s passport would run out in August and entreats the Duce to step up the searches. “Excellence, [my son suffers from] a disease caused by noble studies, perhaps perfectly curable but destined to worsen without remedy if left untreated; only Your powerful intervention can decide on the fate of the searches and the life of a man.”65

The folklore has Mussolini shouting to Bocchini, “I want him found!” extending a commanding arm and an accusative finger to emphasize the order.

Recall, if you may, that these events took place after the catastrophic vertex of fascism, beyond the point of no return, an alliance with Hitler already in place, racial laws being implemented, the aftershocks of a devastating war in Ethiopia still reverberating, only a year or so from all-out cataclysm. Bocchini must have thought, “Oh no . . . there goes that lunatic again.” He wasn’t going to endure another of His Excellency’s eccentricities. As far as he was concerned, Ettore had obviously committed suicide.

A year later, on April 4, 1939, Ettore’s file is closed, with no comment other than: “Archive and strike off.” Two years later, Bocchini was poisoned by Mussolini for openly opposing the alliance with Nazism.

Gilda Senatore was ill for most of the rest of 1938, so she didn’t regularly turn up at the university. She only found out much later that the university had lost all hope of seeing Ettore return and that it was preparing to replace him. All the while, she kept the box of notes Ettore had left her, waiting for him to return. But of course he never did.

She was so ill that she only graduated in 1939, a year after her colleagues. Her father, predictably, didn’t come to her graduation. But her kind uncle did. Of her colleagues in Ettore’s class, only Sciuti became a physicist, in Rome. Gilda also wanted to pursue a career in physics, so she began work with Dr. Cennamo, the assistant professor whose name Ettore misspelled in his earlier letter about Naples. For a while, Gilda taught at the University of Naples. Then she became engaged to Cennamo and later married him.

I understand that she had a very tough life during the war, which she doesn’t want to talk about. Painful memories she’d rather not mention, of the times bombs fell in Naples like rain. She’s very much the survivor, but still a traumatized survivor. After the war, her career derailed. She never returned to her job at the university. Carrelli apparently didn’t approve of married couples on his staff. She had five children; her youngest daughter is just like her.

At some point after she became engaged to Dr. Cennamo, Gilda mentioned Ettore’s box of papers to him. It was the first time she had talked about it to anyone; you can see her dilemma, either way she was betraying someone. Alarmed, Cennamo ordered her to give him Ettore’s box so that he could consign it to Carrelli. He was merely playing by the book: The questura had named Carrelli as the official custodian of Ettore’s belongings in Naples. Reluctantly, her heart full of misgivings, Gilda gave away the treasure entrusted to her by Ettore. And whatever was in that box, trifling or exceptional, science or poetry, related to the neutrino or to love, it was never seen again.

In the background a fireplace is ablaze. It feels cozy, and we are in the Tuscan countryside. It’s February 1990, and the old man who talks to the camera in Bruno Russo’s documentary won’t live much longer. He smokes a rollie and enunciates his words clearly, gripping us with his remarkable storytelling. His eyes gleam incongruously in his aged, wrinkled face. It’s Giuseppe Occhialini, the famous experimental physicist, notable for the discovery of the positron (with Anderson and Blackett) and the pion. He met Ettore Majorana only once, quite by accident, when his ship stopped in Naples in January 1938, en route from Rio de Janeiro (where he was teaching) to Trieste. He had a whole afternoon to kill and paid a visit to Professor Carrelli. Then something happened which he would never forget.

As fate would have it, he nearly missed Carrelli, catching him just as he was leaving for lunch. But the professor received him cordially, postponing his meal and showing him around the institute, chatting about their current work. At some point a youth arrived, whom he took to be a student. “Dark eyes, dark hair,” he remembers. He was flabbergasted to be introduced to Professor Majorana, whom he’d always admired as a genius. Eagerly, Occhialini had exclaimed, “But I’ve always wanted to meet you!”

In his Tuscan home the old man takes a puff from his cigarette and pauses to collect his thoughts. The ash at the end of his cigarette is getting perilously long and we can’t help being distracted by it. Is it going to fall and burn him? But it doesn’t, as the old man tells us very carefully how Ettore had responded to his enthusiasm. Smiling at the esteem bestowed on him by Occhialini, he said, “It’s good you came now. Because had you waited another few weeks you would not have found me here.”

The ash is now surreally long and crooked, perched at the end of his cigarette, and there’s another pause in the old man’s speech, this time much longer. His eyes dampen; he takes a series of puffs. At last he begins to talk again: He explains how he had understood at once, that Ettore’s tone had struck a chord in his soul. He relates how when he was eighteen, he’d also contemplated suicide. And that he’d been moved to confess his own experience to Ettore.

When the camera that had closed on his face shows him again from afar we see that the ash from his cigarette is gone, doubtlessly fallen on him. But his jumper is not in flames as he informs us of Ettore’s astonishing reaction to his confidence. Ettore said, “Look my dear Occhialini, there are those who talk about it and there are those who do it. For this I repeat that if you had arrived a few weeks later, you would not have found me.”

Professor Carrelli was nearby doing something else, but he soon came back and they all had to go their separate ways. Occhialini tried to arrange to have lunch later with Ettore, but he had an appointment and couldn’t accept the invitation. They said their irrelevant ciaos of the world and parted forever.

The old man spent that night on the deck of the ship sailing to Trieste, thinking over his moments with Ettore. Months later, he heard what had happened. And like Gilda Senatore and others who interacted with Ettore in his final period, his most obvious feeling is guilt, no matter how senseless and absurd. He remembers those moments “like one recalls when one met a girl and fell in love for the first time,” a recollection made of “indelible ink,” that stays with you forever and can be summoned at will. And he feels remorse.

By now he’s using the ashtray, still chain-smoking. “We have all met complete strangers on a train who told us incredibly intimate things for no reason. We didn’t meet for very long, but I felt that we were very close. And in that phrase ‘there are those who do it’ I felt the utter misery that was going through his soul.” He feels like “a clown, someone who deigned to talk about suicide without truly meaning it to someone who did mean it.” And when he heard the details of Ettore’s scomparsa , he couldn’t help thinking of Jack London’s Martin Eden and his “death by water.” The obsession with the sea mingled with that for death.

Like Martin Eden, Ettore was a good swimmer. His “watery embrace” would have been a slow and gradual diffusion into nature. If Ettore belonged to “those who do it,” he went back slowly “by water” to the great dance of the cosmos, where time flows in both directions, as for his neutrino, back and forth, forth and back, to-ing and fro-ing. . . .

Colors and radiances surrounded him and bathed him and pervaded him. What was that? It seemed a lighthouse; but it was inside his brain—a flashing, bright white light. It flashed swifter and swifter. There was a long rumble of sound, and it seemed to him that he was falling down a vast and interminable stairway. And somewhere at the bottom he fell into darkness. That much he knew. He had fallen into darkness. And at the instant he knew, he ceased to know.