TWENTY

The Quiet Before the Storm

In the first days of 1938, just after Epiphany, Ettore arrived in Naples, that exuberant city split between extremes of luxury and squalor, one quarter grotesquely peopled by very mature prostitutes, the next replete with ostentatious villas overlooking the gulf and surrounded by colorful flowers. “See Naples and die,” goes the double-edged adage; in the old days Naples was the summit of the rich person’s European tour—but also where many a genteel traveler died from disease or knifing.

Ettore went to Naples, and “he went to Naples willingly,” as his sister Maria stressed in a TV interview many years later. He seemed upbeat, even enthusiastic, probably realizing that this was his last chance to rejoin ordinary life and break away from his family. He took up lodgings at one hotel, then moved to another, then yet another. He paid a visit to his boss, Professor Carrelli, and they instantly became friends, going together to buy his new office furniture (gracefully paid for by the university).

However, Ettore was not so keen on the formal pomp of an inaugural lecture. But the powers that be insisted: On Thursday, January 13, he had to deliver “La Chiamata” or the “Lectio Magistralis,” as they called it in Naples: a lecture with no students in attendance but before the rector and the most important staff. As per custom, the newly appointed professor had to show off his ability to pontificate. The tradition was hated by all and was abandoned in the humanities only well into the 1990s. But in physics, Ettore was the last appointee who had to endure it. In spite of his repeated requests for reserve, his whole family turned up. His lecture, on the foundation of quantum mechanics, was a success.

Ettore’s registration form at the University of Naples. Health: somewhat delicate.

In the period that followed, we learn from his letters that he was slightly disappointed by what he found in Naples. “The Institute is reduced to the person of Carrelli, the old helper Maione and the young assistant Caccemo. There’s also an old Professor of terrestrial physics, who is most difficult to locate.” He tellingly misspells the name of the young assistant (Cennamo). I doubt he deliberately antagonized anyone, but the meager staff was comprised solely of experimental physicists, mostly of the classical persuasion, at that. He must have turned on his snobbery from day one.

He also discovered that he had only five students—not unusual in physics in those days; Rome had about twelve. And “it was in front of this audience of vaguely terrified youths that I presented Prof. Majorana,” as Professor Carrelli related. “After which he started at once with his lesson.” Looking at his lecture notes, we can’t help feeling awe but also an element of the laughable. His students simply didn’t stand a chance of understanding a word of it. He threw at his poor pupils an up-to-date course full of recent discoveries in quantum field theory and mathematical physics. It’s an amazing course, the sort we provide nowadays—some seventy years later—as an optional subject for elite final-year students. I’m sure no one back then had a clue what he was talking about or could possibly have appreciated the value of his efforts.

Still, Ettore wrote that he was “happy with the students, some of whom seem resolved to take physics seriously.” Given the size of his class, he lectured in a small room—an auletta—situated on the ground floor of the institute. He entered from a lateral door giving onto a long, dark service corridor. With the students already installed in their seats, he arrived “silent and serious, not looking at anyone.” He would climb up to the cattedra and without preamble start his lecture. His face “usually so gloomy then brightened up.” The blackboard filled with formulae, his fluid, steady writing assisting an even sharper mind. Judging from his notes, the explanations he presented were original, modern, and crystal clear.

One of the last photos of Ettore, circa 1938.

But often no one understood him—and he realized it. He then stopped, smiled, “forgot perhaps the great scientist that he was,” and tried to help the students, seeking alternative, simpler explanations, even leaving the cattedra in his efforts to make himself understood. His students are unanimous in saying that although they couldn’t follow him, “Professor Majorana was very generous and big-hearted . . . always tried to help those around him.”

And so, after all those years locked in his room, Ettore settled into a routine away from his family. He led a quiet life of hard work and tranquility. In fact, there’s very little abnormal in what is documented of this period. He wrote that he found Naples a bit odd because of the “scarcity of cars.” (!!!!) His letters to the family are full of platitudes and details of practical chores. On February 23, 1938, he wrote to his mother in his trademark deadpan, “I have a discreet room; today they’ll give me a better one overlooking Via Depretis from where I’ll be able to see Hitler passing in three months. Are you cured from your cold? Perhaps I shall visit during Carnival.” On March 9, so close to his final crisis, he wrote again to his mother, “Here the weather is very beautiful, ideal to sail in the gulf. . . . I shall perhaps visit on the weekend.”

Chilling, if we reread this with the benefit of hindsight. He won’t see Hitler passing on Via Depretis in three months, and he knows it. “Sailing in the gulf” will soon be dressed with a different, macabre meaning. At this point, he had already made his “decision by now inevitable.” In fact, he had even confessed it to someone. He had also begun taking care of the logistics, all of a sudden withdrawing five months of salaries he hadn’t previously bothered touching and asking his mother for his full share of their bank account.

On the surface, however, everything looked incongruously normal in Ettore’s life, just like the quiet before a storm. Carrelli reported that he seemed very busy, “working on something absorbing, which he preferred not to talk about.” He lectured in the morning on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays but rarely put in an appearance at the institute otherwise. He worked hard, alone in his hotel room, or so everyone thought.

Then on Saturday, March 19, six days before D-day, he sent a bland letter to the family cancelling the visit he had promised the week before. He stated that he couldn’t come because he had “business to attend on Monday at the names registry and elsewhere.” He sent a telegram to ensure no one was waiting for him in the evening, and assured the family that he would visit “for sure” on the following Saturday. There is nothing unusual in his handwriting or style, and the family saw nothing strange in it. What a masterpiece of deceit!

His family expected him a week later. Which is, of course, when it happened, the run of events kicking off on the morning of Friday, March 25, when against his habits, Ettore visited the university on a day he didn’t lecture. There he met one of his students, Gilda Senatore.

Gilda . . . a woman doing physics in 1938?

Oh, yes—I forgot to mention one little detail. In a deeply chauvinistic country and at a time when women weren’t supposed to go to university, let alone study physics (recall Maria Majorana’s experience), four of the five students who attended Ettore’s course were women. And the last person he willingly met was one of them.56

These days, Dr. Gilda Senatore is best known for being the last person to see Ettore Majorana—or at least the last one he saw of his own accord—but the story of her life is interesting in itself.

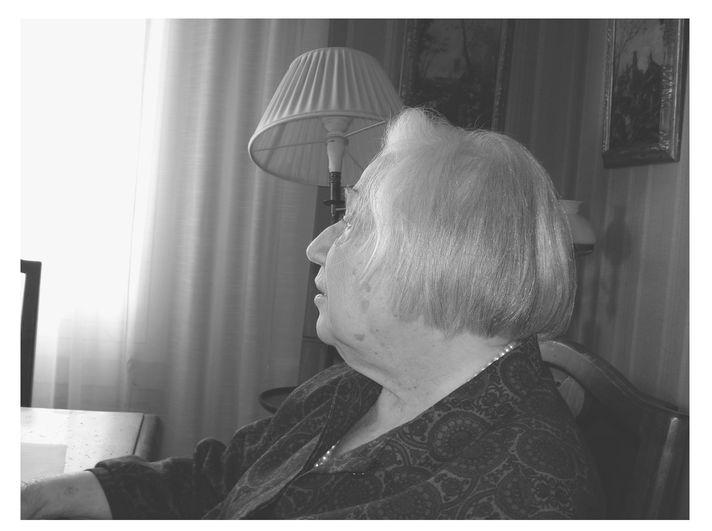

When I meet Gilda in Naples, at the respectable age of ninety-four, she’s still a force of nature: very talkative, extremely articulate, with remarkable lucidity. She’s fond of purple prose and thumps her fist on the table with remarkable vigor (the first time she did it, I started with surprise). She holds my hand and looks me in the eyes frequently. Apart from the inevitable eccentricities of a ninety-four-year-old, she is in superb form.

The profile of Dr. Gilda Senatore, at the age of ninety-four.

Born in Brazil of Italian parentage, Gilda spent her childhood shuttling between São Paulo and what she terms “the jungle,” as the family followed her father, who worked in the mining industry and had to spend months on end in the wilderness. As we talk over lunch, I surmise that she still retains the fondest memories of these “undomesticated beginnings.” She confesses to loving snakes even after reporting several chilling encounters57; she excitedly recounts how she’d vanish from the house to chase huge lizards in the forest with her Indian friends; she cherishes telling me, “I was breast-fed by an Indian woman, so I became a little savage.” Perhaps due to these early experiences, she became a rebel as she grew up. This trait was to have a powerful effect on her destiny.

It must have been a shock to young Gilda when at the age of eight she was transplanted to Cava de’ Tirreni, a tiny village south of Naples, and suddenly demands that she behave like an European were sternly made of her. She responded by adding an intellectual element to her brattish ways, making a nuisance of herself at school. She dropped ink on her immaculate white school uniform just to see the beautiful fractal develop, then asked why the fractal was the way it was, what light was made of, etc., etc., etc. . . . pestering the teacher with science questions he couldn’t answer. Impertinences so unbefitting a young lady that her teacher punished her with a pair of donkey ears; to which she replied, “O burro és tu,” amusing herself to death when the poor man reported to her father her “peculiar fondness for butter.”58

From the level of her questions, it’s obvious that she was a physicist in the making. But with the air of the motherland, her father turned into a severe traditionalist, becoming a major hurdle for her talents. According to Gilda, he vented his view that “all women in my family can either be housewives or seamstresses.” Gilda was not interested in either. And so determined was she to study physics at university that when her father threatened to disown her for her stubbornness, she retorted that she was ready to be thrown out. It can’t have been an easy decision and all these years later, when I tell her the story of Maria Majorana’s failed attempt to go to university, she becomes very agitated, stamping the floor for emphasis and thumping heartily on the table.

In the end, matters were made simpler for Gilda by the intervention of an illuminated uncle (a top doctor in the region), who offered her housing and paid her fees while she studied. She still had to give private lessons to fully support herself, but she did manage to attend university.

At university, Gilda informed Professor Carrelli that she felt honored to be offered the chance to study with such an eminent physicist, but unfortunately she couldn’t care less about experimental physics, Carrelli’s field of expertise. Theory, mathematics, and modern physics were her interests. Carrelli, half amused and half annoyed, passed her on to his colleague Professor Majorana.

Which is where presenting another facet of Gilda’s person becomes absolutely indispensable. How shall I put it?

I don’t want to diminish the fact that young Gilda Senatore was very intelligent and had a strong, resolute character. That is a fact, and I couldn’t stress it more. But it is politically correct crap when you go around talking to intellectuals who know and have studied her story, and they all fail to mention a very important little detail. A crucial piece of the story. Absolutely essential. It took an old-style Italian professor59 to take me aside and break the news to me:

Gilda Senatore was a bombshell of a woman. The type that stops married men on the street even in the company of their wives, causes lethal car crashes with the casualties going to heaven still smiling—a female typhoon! All these years later, she still elicits comments such as the unnamed professor’s: “As a man something inside you broke wild when you saw her; your heart started to race; you lost your head completely.” She was, as they used to say in old-fashioned Italian, a vampa: a heat wave.

Is it un-PC to point this out? Being attractive hardly precludes being clever, for a man or a woman. In fact, Gilda herself is as proud of her juvenile beauty as she is of her intellect. When we met, one of the first things she told me was her “three measures” when she was young (bust, waist, and hips). But such is current Italy.60

Now we all know the troubles Ettorino had with women, the obsessions and complexes that vexed him. It must have made for some amusing viewing to watch the spectacle of Ettore entering the auletta only to find that four out of his five students were nubile young women and that one of them was terminally attractive. It’s a measure of his remarkable talents that he managed to fill the blackboard with the intricacies of quantum theory while his mind may well have been elsewhere. And it’s significant that the only student mentioned in Ettore’s last letter to Carrelli is Sciuti, the only male, who by all accounts had been totally irrelevant to him.

Given this state of affairs, it is not surprising that Ettore almost avoided Gilda Senatore. As Gilda comments, “He walked glued to the walls, like a shadow. Even the janitor commented on this.” It’s obvious that the whole department was affected by her, but no one more so than Ettore, with his patent need for love, repressed below so many layers of self-deprecation and low self-esteem. She must have represented the only plank of salvation possible in his sea of desperation. As his eponymous nephew said, “Love would have made all the difference.”

Gilda was kind to him in a totally innocent way. But needless to say, he was far too shy to voice his feelings. He must have blushed, played the innocent love-struck boy, but no more. More generally he refused all contact and communication, with her or with anyone else. He was very solicitous in helping his students and her in particular, but he’d refuse anything in return, any form of affection in repayment for all he was giving them. “He was a very solitary man,” Gilda sums it up. And so they hardly ever talked to each other. Until the day Ettore disappeared.

On the morning of Friday, March 25, 1938, Gilda Senatore went to the university to attend a lecture on terrestrial physics, after which, as she often did, she remained in the lecture room to study.

Suddenly she heard her name being called:

“Signorina! Signorina Senatore! . . .”

She raised her head and saw beyond the lateral door, still in the access corridor, Professor Majorana, that taciturn lecturer who never addressed any of his students and never turned up on the days he didn’t lecture (of which Friday was one).

A bit taken by surprise, she didn’t move, waiting for him to enter the room and talk to her. But he didn’t budge either, expecting her to come to him. And when she didn’t, he backed off slowly.

Something made Gilda get up at once. She ran to the doorway and then down the penumbra of the corridor. She quickly caught up with him and asked anxiously:

“What is it, Professor?”

Ettore stopped and looked at her fixedly. Something was obviously wrong. Gilda can’t quite explain what, even after all these years and knowing now what happened next. But he just said:

“Here!” and placed a large box in her hands. “Here, Signorina! Will you please keep these papers for me?”

Startled, she took the box and began to seek an explanation. But he cut her short with a gesture, adding gently:

“We’ll talk about it later.”

And without letting her speak, he disappeared down the corridor, briefly waving her a goodbye.

She stayed there, frozen, wondering what to do with that box in her hands, while Ettore moved away, his reality already disintegrating. Later she will talk about this event very extensively: in TV interviews, in various writings, to me. And the major inflection patent in her tone is guilt: unexplainable, unjustified guilt, of the sort that is not appeased by others insisting that it wasn’t her fault. Guilt for not having stopped him, for not having done something to help him. But, as she puts it herself, he wasn’t susceptible to receiving. “Prof. Majorana liked to give generously, with simplicity and humility,” she says. “But he would shy away as soon as anyone tried to give him anything.”

I don’t know what she thought she could have given him, when she reported these tragic moments so many years later. But even knowing full well how inaccessible he was, she still feels she could have done more, done something to stop him.

“Perhaps he wanted me to say something else to him, to extend a hand, to help him out.”

Because he must have been wretched, miserable, depressed to the point of desperation. A drowning man flinging his arms out of the water one last time.

“But he didn’t give me time.”

And thus began the storm.