EIGHTEEN

The Crepuscule of Via Panisperna

Despite the uranium oversight, the work carried out by Fermi and the Boys in 1933 and 1934 is astonishing, the sort that requires a unique environment, realized as if by magic, an accident that occurs perhaps a few times in a century. But after such exuberance comes necessarily a hangover, a come-down. And by 1935, the Via Panisperna Institute was in a state of decline, the mood lethargic, in sharp contrast to the earlier overdose of enthusiasm. Segrè one day asked Fermi:

“You are the Pope and full of wisdom. Can you tell me why we are now accomplishing less than a year ago?”

Without hesitation Fermi replied,

“Go to library. Pull out the big atlas. Open it. You shall find your explanation.”

As legend has it, the atlas opened “of its own volition” on the map of Ethiopia. This was indeed the answer. Dark forces were in action that couldn’t be ignored.52

Around this time, the Boys started to disband. Pontecorvo moved to Paris, Rasetti to Columbia, and Segrè—having tempered an adequate number of tuning forks—was rewarded with a professorship in Palermo. None would ever return, leaving Fermi and Amaldi to toil on their own. New hires—such as Giancarlo Wick—good as they were, didn’t quite re-create the original atmosphere. That unique state, “where two and two make more like ten” vanished, a prosaic four replacing it. They were still good; but they were no longer miraculous.

Then, on January 27, 1937, Senator Corbino suddenly died from pneumonia at the age of sixty-one. His unexpected demise left the Boys prostrated, and while they were grieving and making eulogies, no one had the presence of mind to initiate the political maneuvers necessary to install Fermi as his successor. Antonino Lo Surdo, therefore, had the last laugh in his feud with Senator Corbino, when the university rector—a stout Fascist like Lo Surdo—invoked an arcane piece of university legislation to bypass the faculty and appoint him Corbino’s successor. Even though Amaldi was given Corbino’s chair, Lo Surdo’s appointment was a “sign that Fermi’s fortunes were declining in Italy.” But the reasons ran deeper than Corbino’s death: The trouble was that the political situation was deteriorating dramatically. The Fascist joke had turned sour, was indeed not a joke at all now, if it ever had been.

It was oracular that that atlas had opened at the Ethiopia map (or perhaps it opened there from overuse). Fascism began as a populist movement, stirring national pride and promoting economic progress; but in 1935, it moved up a gear. The exaltation of imperial Rome was part and parcel of the fascist ideals, but this had materialized as nothing more than rhetorical bullshit. In October 1935, however, in an act of gratuitous belligerence, Italy invaded Ethiopia. There was little strategic or economic gain; a lunatic reenactment of the Roman Empire or a petty revenge seemed the only possible justifications.53 The “gesture” was so ridiculous it would have been comical were it not for the numerous casualties, some horrendously gassed by Italian troops (in violation of the Geneva Protocol). But if the corpses of the heroes and their victims were a local catastrophe, there were also disastrous diplomatic effects.

The “Abyssinian Affair” put Italy at odds with France and England—its allies—and the League of Nations predictably imposed crippling economic sanctions. In dire financial straits, Mussolini responded with demagogy: With acts of extreme symbolism but little value, such as his appeal that Italian women voluntarily donate their gold wedding rings to save the motherland from bankruptcy. Women from all walks of life—including Laura Fermi—complied. Such gimmicks above all assured the tacit popular approval of the regime, despite its growing tyranny. No one dared to complain.

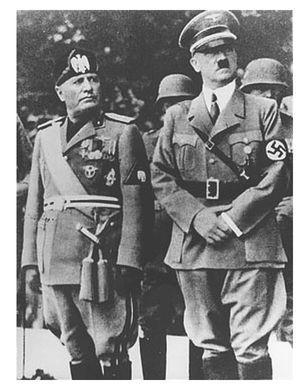

Mussolini and Hitler in joyous partnership, circa 1937.

Naïve, no doubt; but such regimes thrive on people’s sheep instinct combined with their fear of compromising their well being. And who can cast the first stone? Every time I see someone in our “democratic” world refusing to fight for justice (against a tyrannical boss, a big company, etc.) for fear of losing their comforts, I think, “You don’t know it, but in different circumstances you’d have accepted a job in Auschwitz.” Having met those who fought fascism in Portugal despite the constant threat of prison and torture, I never cease to be amazed at how “adaptable,” lacking in cojones, “normal” people can be. Fascism feeds on that.

Italy’s estrangement from its traditional allies meant that realignment with Germany was now inevitable, and it officially happened in October 1936. And this is when most of Mussolini’s aides began to think he’d gone soft in the head. Germany was Italy’s archenemy, until then to be opposed at all costs. Furthermore, such an alliance meant partnering up with Hitler, who had obvious imperialistic designs of his own. With the delusion characteristic of all dictators, Mussolini nourished the view that Hitler was his puppet. He was able to maintain this perspective while Italy fought side by side with Germany in the Spanish Civil War. But his fantasy ended sharply in 1938 with the Anschluss, or Austria’s annexation by Germany.

One day, Schrödinger—an Austrian—presented himself to Fermi in Rome in great disarray. He’d fled from Graz after the Anschluss, on foot and carrying nothing but a rucksack. He begged Fermi to take him to the Vatican to seek protection, which Fermi duly did. Schrödinger had antagonized the Nazi regime sufficiently to be in serious trouble, having resigned from his prestigious Berlin Chair when Hitler came to power. With the help of Irish prime minister Éamon de Valera, Schrödinger found solace in Dublin.

Italy had defended the Austrian border against Germany in 1934, and Mussolini regarded himself as Austria’s protector. When Hitler invaded without consulting him, everyone must have understood exactly who was in charge. Benito bit the bullet, and a new phase began in the balance of the Powers of the Axis.

Italian Fascism—with its idealistic streak—had been detached from the racism and anti-Semitism raging throughout Europe. Aware that he could now do whatever he wanted, Hitler requested that the German racial laws be adopted in Italy. Imagine the mess this caused for the state philosophers, including Gentile Sr.! Idealism precluded racism on the grounds that the essence of man is the soul, detached from the body and so from race. Two remarkable tasks were now posed to the fascist ideologues: first, a proof that the soul in fact had a race, contrary to previous assertions. Second, the even more ludicrous demand that they demonstrate that Italians from all provenances, including Sicilians and Sardinians, were Nordic Aryans.54

The hoops they had to jump through to comply with the führer’s demands. . . . So far did they bend backwards to twist logic that it must have been universally obvious they were, in fact, bending over. The resulting literature is so ridiculous that in spite of all the pressure, few university professors could bring themselves to undersign it. Even those who did—among them the brain of fascism, Giovanni Gentile Sr.—expressed strong reservations. The corollary, “Jews do not belong to the Italian Race,” was the predictable mess of unenforceable laws. Every Italian is “a bit Jewish”; for example, Rasetti could be described as a borderline Jew. Pontecorvo and Segrè were fully Jewish, but none of the Boys was exactly pristine, with the possible exception of the Sicilians (including Ettore and Gentile), who are racially Arabic in no small measure, and thus “deplorably Semitic,” too.

These absurd laws would have surprised people were it not for the fact that they arrived amid a deluge of tripe, confirming that the great dictator Mussolini was well in the throes of insanity. There were now laws forbidding men from wearing ties, lest they might press on a given nerve and prevent them from aiming a gun properly. Bachelors were barred from certain public-service jobs (with the implication that they were necessarily gay). Of the three ways of saying “you” in Italian, the form “Lei” was legally banned.55 Children of tender age were indoctrinated in the coincident virtues of reading books and shooting guns.

Hitler visited Rome in May 1938, when it was clear to all that Mussolini had become his bitch. Patchwork reconstruction of a dilapidated Rome led to an expressive popular poem:Rome of travertine grandeur

Patched with card and plaster

Salutes the little wall painter

As her next boss and master

Fermi is reputed to have commented that Italy could now be saved only if Mussolini became overtly mad and went out to a major square on all fours barking like a dog. But Fermi was under attack, accused by the fascist press of “turning the Physics Institute into a synagogue.” His Jewish wife was baptized in a hurry, but her father (a Navy officer) was dismissed from service, showing that notice of her origins had been taken. So when Niels Bohr took him aside at a conference to inquire if this was a good time for him to receive the Nobel Prize (which would provide him with the necessary finances to escape Italy), Fermi accepted. And when he went to Stockholm to collect his award, never to return to Italy, the era of the Boys of Via Panisperna was formally brought to an end.

Just before their final sunset, however, an incident occurred at Via Panisperna that would have a dramatic effect upon Ettore’s life. At the start of 1937, shortly after Corbino’s death, a concorso—a competition—was announced for a cattedra in Palermo, where Segrè had moved. This was the first time, since Fermi and Rasetti had been appointed ten years previously, that a large-scale series of appointments was made. The process was to be characteristically simple: In Italy the winner is always known before any such competition starts, the rest being merely a bit of theater.

Whoever ranked first would take up the Palermo position. But second and third places would also receive an appointment, with bids to be made by universities across Italy. The expectation was for latter-day Boy Giancarlo Wick to come first, Giulio Racah from Florence to place second, and Giovanni Gentile Jr. third. Wick should stay in Palermo for at least a year (transferring later if he so wished), so that Palermo didn’t lose its new position. Pisa and Milan would provide for second and third places.

It’s not clear how much coaching was needed, but Ettore pulled himself out of the slough of despondency in which he’d been immersed for four years and decided to apply for the Palermo position. Some claim that Amaldi insisted repeatedly, others that Ettore’s application came as a complete surprise. Whatever happened, his application left those in charge of making a decision flabbergasted. In fact, it created severe logistics problems.

No one doubted that Ettore should now come first, but then if the previous ordering was kept, Ettore’s friend Giovanni Gentile Jr. would be left without a job. His powerful father would not be amused. Also, Ettore’s appointment to Palermo would be extremely awkward for Segrè, who hadn’t spoken to him since Ettore’s disgraceful 1933 letter from Leipzig. Could Ettore have been playing a prank on Segrè? He surely may have been annoyed by Fermi and Rasetti yet again making plans which excluded him. But why would he upset his friend Gentile?

Quite possibly he wasn’t trying to annoy anyone, and above all had strong personal reasons for applying. After four years hiding in his bedroom, he may have launched a desperate attempt at reconciliation with the normal world, severing his suffocating relations with mother and family. Ettore took great care with the preparation of his CV: The draft has survived and we see that much thought went into it. For example, he crossed out his “Dr.” title, replacing it with “Prof.” He even submitted a new paper in support of his application. This—his last—paper, has left us reeling about the neutrino to this day.

On October 25, the circus began in earnest. At 4:00 pm, a commission assembled consisting of Fermi, Carrelli, Lazzarino, Persico, and Polvani. This panel had been selected by the minister of education from an informative list, on which each name was followed by the date the individual joined the Fascist Party. In the initial roll, one can find Ettore’s uncle, Quirino, but he was crossed out to avoid a conflict of interest. After “exhaustively exchanging ideas,” the commission unanimously deliberated that Professor Majorana had a national and international scientific standing of “such resonance” that he should be appointed to a new chair to be established in Naples “by exceptional merit” and independently of the concorso. The competition was thus suspended until the case could be reviewed by the minister.

The term “by exceptional merit” had a technical meaning. It was an instrument of Italian law which permitted the appointment of an outstanding candidate to a professorship, dispensing with the usual formalities. It had been used a couple of years before to allow Marconi—an autodidact who’d never been part of academia—to be appointed to a chair in Electromagnetic Waves at the University of Rome. It would have been embarrassing to see a Nobel Prize winner, devoid of academic training, fail the exams.

The minister of education—perhaps after some oiling up by Giovanni Gentile Sr.—duly ratified Ettore’s appointment at the University of Naples. The initially planned course of events could now resume, and when the concorso commission met for a second time, Wick was appointed to Palermo, Racah to Pisa and Gentile Jr. to Milan. Order was reestablished, with everyone suitably accommodated. Fermi was happy with the outcome but felt intensely annoyed by the shoddy administrative work (for which he may have blamed Ettore). In what I’m told is one of the most illegal things that can be done in Italy, he renumbered the second meeting as number one, thus removing the first meeting from the records.

Ettore was delighted with his new job. On November 16, 1937, he wrote to his uncle Quirino: “I’ve laughed a bit about the odd procedures in my appointment, which I didn’t even suspect. I hope that I’ll truly get to Naples.” And to Gentile, on November 21: “I’m in great relations with Carelli. . . . Even Segrè and all the others have been very nice. I’m surprised, in whatever concerns me, with your doubts regarding my good stomach, in a metaphoric sense. Pio XI is very old, and I have received an excellent catholic education; if on the next conclave I’m made a Pope by exceptional merit I’ll accept at once.”

With retroactive effect from October, Ettore was bestowed with a highly prestigious “VI grade A” chair at the University of Naples, on 29,000 lire per annum, a larger-than-normal salary. And thus began his final stage on the bright side of the moon.