FIVE

Bread and Sperm

An electric wire snakes from a laboratory window and climbs up a wall toward the roof, where it loops around the finger of a classical statue pointing vaguely to imperial Rome. The wire then disentangles itself from the marble digit to fly freely into the blue skies, aiming for the orbs, the supralunar universe, but stops at the beck of a fat balloon, hovering calmly above the building.

From down in the lab comes a cacophony, the discordant noises of mistuning. This exasperates a bespectacled young man, a nerd from the first pressing:

“Shit! Fuck! Shit! This fucking shit isn’t working again!” The abuse flies across the lab, catching the attention of another standard-issue nerd. He looks at a sheet of calculations, scribbled mad professor-style, fixes a number here, adjusts a knob there, mumbles, and finally releases a powerful hammer-fist of frustration on the desk: “Better go call Majorana.”

And off they run, like two kids, through the streets of Rome, bursting noisily into a lecture hall not far off. By the blackboard the professor stammers: “Sine of twent . . . er, no, cosine of twenty-five, which gives us, er . . . which gives us; no, cosine of forty-five, which is zero . . . no.”

Unflattering comments pour from the auditorium—everyone is amused. Everyone except one young man, sitting apart from the others, evidently pained by so much incompetence. The nerds from the lab zero in on him and whisper: “Ettore! Give us a hand with this.”

He briefly looks at the nerds’ misguided labors, then at the professor; he jots corrections on the paper given to him but has hardly finished when he looks up and shouts, “No!”

He drops the sheet, storms to the blackboard, grabs the chalk from the old man and:

“That’s how it’s done. See?”

A silence falls. The old man is speechless, and so is the class. Availing themselves of the thick embarrassment, the nerds gather up the sheet of paper with Ettore’s corrections and escape from the classroom. They dash back to the lab where they readjust the equipment, following Ettore’s revised figures.

“It’s working! It’s working!”

“That Ettore is a genius!”

A clear sound is finally heard.

Not far from where these events are taking place, at a radio station an important ceremony is about to begin. An orchestra plays, microphones collect its harmonies, the ether carries them for the benefit of whole universes, present and parallel. Formally attired gentlemen preside over a table on a stage. And there’s a lectern, begging for a speech.

The orchestra continues its performance as the speech is introduced by a comely young lady:

“Italiani, amici. . . .”

Another formally attired gentleman enters the room, radiating dignity, valor, accomplishment; the comely lady corroborates this impression:

“With the audacity of Christopher Colombus, the genius of Volta, the strength of the Caesars . . .”

We are talking about no less than the Cavaliere, the Honorable, the Valiant Guglielmo Marconi, the Italian superstar inventor, second not even to Christopher Colombus—even if half-Irish, from the whiskey-producing family Jameson, but made the more Italian by being a personal friend of Mussolini, and rumored to be working on a death ray capable of instantly carbonizing hordes of black undesirables in Abyssinia, carrying Italy anew into exalted Imperial Glory.

But today we’re merely celebrating an anniversary, the many years since electric wire has become a redundant accessory in this battle we fight to be heard by the entire universe. And Marconi, as the inventor, is to be glorified.

Ettore has by now gone home, following his lecture-room outburst, where a middle-aged lady is listening to Marconi’s ennoblement in the living room.

“Switch that radio off, Mother! Do you want to make me lose my temper?”

She lowers the volume—and smiles—only to raise it again as soon as he’s gone. Ettore has hardly reached his room before he hears a loud whistle from the radio. A terrible screech of feedback and interference: an electronic misfortune! Ettore frowns: How could they have let this happen, at a moment of such importance? At the radio station we see the engineers sweating profusely, readjusting knobs. The Cavaliere looks on, slightly disgusted. Who’s going to be blamed for the debacle? But a young radio engineer—knowing he’ll probably be singled out as scapegoat—has already found the answer.

“A very strong signal. From Via Panisperna. . . .”

At the lab, the nerds are blasting their signal at full strength; up in the skies their balloon, serving as an antenna, shivers with effort. The cacophony on the radio finally subsides as the nerds take over the transmission with a perfect twin of the earlier broadcast. The orchestra has been replaced by a gramophone playing the same music at the lab; and they have their own comely young lady who mimics:

“Italiani, amici. . . .”

But the music now smoothly shifts into a funeral march. At the radio station, the apprehension mounts, as they listen impotently to a broadcast that isn’t theirs.

“We have terrible news for you.”

The funeral march gets louder, more dramatic.

“Guglielmo Marconi is dead!”

The cavaliere allows his jaw to drop.

“With him, Italian physics dies!”

In his room, Ettore chuckles. So does everyone at the lab.

Later, the nerds burst into Ettore’s office at Via Panisperna.

“Ettore, Ettore! The police are interrogating your mother!”

He grabs one by the throat:

“Why did you tell them?”

“We didn’t. Let me breathe, Ettore!”

He briefly releases the pressure on the nerd’s throat.

“They said that only you could have broken into the transmission.”

Ettore places his head between his hands:

“Oh, my God. How am I going to face Mother now?”

He hears giggling—the nerds are already in full flight. He chases them, but they benefit from a head start. They run and cackle, shouting back to him:

“Only Ettore Majorana could have killed Cavaliere Guglielmo Marconi!”

“With him, Italian physics dies!”

Apocryphal, no doubt, but true to the spirit of the physics institute set up by Senator Orso Mario Corbino at Via Panisperna, Rome, in 1926. The scene comes from Gianni Amelio’s film I Ragazzi di Via Panisperna (The Via Panisperna Boys). That’s the tag by which the young physicists became known. The Boys’ knack for atomic and nuclear physics would place Italy at the forefront of physics for the first time since Galileo. What a mess they made of it!

One can almost hear the arguments Ettore had to endure at the Café Faraglino, as his friends tried to convince him to join the Via Panisperna Boys:

“But what are you doing sitting in engineering lectures, bored to death by those ‘braying donkeys,’ as you put it yourself?”

Senator Corbino had issued an appeal to all bright students in Rome to come and join his institute, where a very young Enrico Fermi was already installed in the safety of a cattedra. And Emilio Segrè, one of Ettore’s friends, had answered the call.

“At Via Panisperna you’ll be in the company of other geniuses.”

Except that Segrè was anything but a genius, and Ettore knew it. Flattery is often a proxy for self-flattery.

“Come on. I’ll introduce you to Fermi. You’ll be enthused.”

And that was how a reluctant Ettore first came to be a Via Panisperna Boy.

The Via Panisperna Institute was a bona fide scientific brothel, by all accounts. Pranks, bets, mathematical races, and the like abounded. Unless you’ve done science yourself, it’s not what you’d expect of scientists at work. But that’s how real science is done: in a climate not dissimilar to “Surely you’re joking, Mr. Feynman.” A typical prank was to steal Fermi’s car keys, park the vehicle elsewhere, then replace the keys before their absence was noted.

“Did you forget where you parked your car, Enrico? All that mathematics must be hurting your memory!”

A brief preoccupied silence would befall the great Fermi. Then, suddenly:

“I want you to put my car back where it was. Now!”

And they’d smear him with laughter—for a split second, they’d caught him.

“Things like that happened all the time,” Boy Franco Rasetti stated many years later. With Fermi barely seven years older than the youngest of his students, they were more like friends than colleagues. They called each other by the informal tu, played tennis at lunchtime, and went walking on Sundays. Concomitantly, if things went wrong, it quickly became personal.

Relations between Ettore and Fermi grew particularly acrimonious. When they first met, Ettore presented Fermi with the full solution to a tough problem Fermi hadn’t been able to solve. That incident set the standard: There was a competitive streak in their relationship that became only stronger with time. In Amelio’s film, Fermi allows Ettore into the group without an exam, on condition he doesn’t tell anyone he’s beaten him at algebra. Again, apocryphal—but metaphorically correct.

It was common to find the Boys congregating around Ettore and Fermi, a difficult mathematical problem laid out for them on the blackboard.

“Start!”

And Fermi would chalk away while Ettore used nothing but his mind, hands in his pockets, pacing and mumbling.

“Got it!”

“So have I!”

The result would be conferred over, the winner declared, and money would exchange hands among the loud entourage. And it must have irritated Fermi a great deal that he often lost. “[Ettore] could easily have been a professional numerical prodigy,” Emilio Segrè wrote. After a while no one computed anything at Via Panisperna: In the absence of computers, if they needed a calculation done, they’d just ask Ettore. “What’s the integral of the exponential of cos x between 0 and 3?” And Ettore would supply the answer. Straight from his mind.

It’s not as if Ettore wasn’t aware of the storm he was whisking up and the effect he had on Fermi. Soon after his induction he wrote in a letter: “At the institute I’m becoming the most influential authority.” Fermi made statements like, “If Majorana can’t figure it out, no one can” (as documented in the memoirs of the other Boys). Or the naked admission, “Ettore is more intelligent than me.” The fact is that Ettore vexed him: In an environment where informality reigned, but where, pranks aside, he was supposed to be the boss, Ettore was the only one who stood up to him. The Boys all agreed that Majorana treated Fermi as an equal, often with haughtiness. Fermi felt humiliated by Ettore’s genius but also by his overall attitude towards science and life. Because beyond his lighthearted side, Fermi had a big complex. Not with regard to women like Ettore, but with regard to science.

As Boy Bruno Pontecorvo put it, “It was typical to note in [Fermi’s] face this childish and guilty smile, when . . . he lost his self-confidence, which happened, for example, in the presence of Majorana, who was endowed with an imposing personality.”

How a pampered genius like Fermi became riddled by an inferiority complex is a very sad story. Who knows how much it eventually contributed to Ettore’s disappearance . . .

The Via Panisperna Institute was the work of Orso Mario Corbino, a bald and chubby Sicilian exuding vitality, with an explosive nature and an iron will tempered by worldly knowledge. It was said that Corbino could with absolute sincerity utter the most unpleasant truths without causing offense. A brilliant and witty orator, twice a minister (of education and of economy) and an eminent personality among industrialists, no one pulled strings as shrewdly as Corbino. It’s telling that he managed to be part of one of Mussolini’s cabinets without joining the Fascist Party. In fact, he amassed and retained enormous influence without ever joining the Fascist Party, which under the circumstances may not be entirely flattering. An ambiguous character, successful in all terrains, he seems to have reserved his moral standings for ends rather than means.*

A famous physicist himself (in Messina and then in Rome) who’d started his career as a modest high-school teacher, Corbino led a double life: on one side his political career, business, and money, and on the other, laboratories and the interests of Italian physics. In 1926, Senator Corbino, then head of the Physics Department of the University of Rome, decided that the time was ripe to set up an institute of physics that would put Italy on the world map. That’s how he began collecting his “Boys,” as he called them.

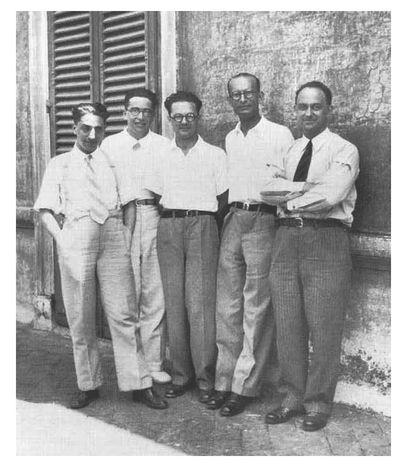

The Via Panisperna Boys. From left to right: the chemist Oscar D’Agostino, Emilio Segrè, Edoardo Amaldi, Franco Rasetti, and Enrico Fermi.

At first the Boys were four: Enrico Fermi, Franco Rasetti, Edoardo Amaldi, and Emilio Segrè. In their inimitable style they attributed nicknames to themselves: Il Papa (the Pope) for Fermi, Il Padreterno (God the Almighty) for Corbino, Il Cardinale Vicario (the Cardinal Vicar) for Rasetti, and Il Prefetto alle Biblioteche (the Library Prefect) for Segrè. Ettore once signed a letter “with cordial salutations in the name of the Pope, the Sacred College, the Seminarists and the Minor Friars.” As we know, Ettore himself was Il Grande Inquisitore—the grand inquisitor.

* It would be easy to heap Mafia slurs on him—connections with the Freemasons or the king might be more realistic—but he was obviously more complex than that. Senator Corbino may have been an opportunist, not overly concerned with the means he used to obtain his ends, but he was too well connected to need to do anything overly dirty. At a time when Italy was undergoing a full transition to dictatorship, it is telling of that country’s intrinsic anarchy that a “free-standing” individual could sail through such troubled waters doing basically whatever he pleased and commanding huge resources.

Corbino being God the Almighty, it was befitting that Fermi should be Pope. Corbino took care of politics while Fermi, his emissary on Earth, was the scientific leader. A fanatic adherent of the recently discovered quantum mechanics, with a well-established international reputation (for the codiscovery of the electron cloud and the Fermi-Dirac gas), Fermi would have fallen victim to the “jealousy of the influential mediocre” had Corbino not intervened. Competing for a position in Cagliari, Sardinia, Fermi was bypassed in favor of someone who’d got his degree almost ten years before Fermi was born. The reason: the majority of the panel was against Einstein’s theories, the subject of several of Fermi’s papers.17 But Corbino swiftly found Fermi a full professorship in Rome before he had time to emigrate. Corbino then set about building up a group around him.

Franco Rasetti—the Cardinal Vicar, sometimes the Venerable Master—was the next to be hired. A sportive and muscular man like Fermi, they pronounced words in the same Tuscan accent, cackled in the same way, and had the same overweening attitude toward women. Fermi and Rasetti had been undergraduates together at Pisa, where they’d become inseparable. The signature humor at Via Panisperna is often seen as a relic from their student days.

To complete his squad, Senator Corbino raided the school of engineering for talent. One morning he announced to his class that Rome was about to acquire the best school of physics in the world. If there was anyone with a solid intellect and exceptional valor, he could step forward. But he “only wanted the best available students, worthy of the time and effort that would be spent on them,” as Fermi’s future wife, Laura, then a student, later related. Amaldi, a cherubic eighteen-year-old (promptly nicknamed Adonis) was the only one with enough courage to do so.

Another engineering student who answered the senator’s appeal was Emilio Segrè. Two years older than Amaldi, he wasn’t in Corbino’s lecture, but later heard about it and transferred to physics. If you’re impressed by the bureaucratic flexibility afforded by Rome University, let me disabuse you: These transfers were made possible only because Corbino told the usual vermin of paper pushers to shut up and go to hell.18

Coming from an extremely rich Jewish family that owned a large paper mill outside Rome, Emilio Segrè looks perfectly nerdy in photographs but is always elegantly dressed, draped in expensive clothes his physique can’t quite support. He was more serious than the rest, and Fermi and Rasetti’s humor irritated him. Indeed he was renowned for his bad temper, as attested by his alternative nickname, the Basilisk. As Laura Fermi puts it, “Just like the legendary serpent, Segrè threw flames from his eyes when he felt offended.” His touchiness left its marks on Fermi’s meeting table, which still has a big hole in the middle where Segrè’s irate fist fell at one point when the others didn’t let him talk. Such were the wonders of Via Panisperna.

Segrè was a good friend of Ettore, and it was he who praised Ettore’s skills to Fermi and introduced him to Via Panisperna. But it won’t take much deduction to realize that Segrè’s character combined with Ettore’s subtle sarcasm was bound to produce an explosive mix. Indeed, on the eve of Ettore’s scomparsa, an all-out vendetta raged between the two. And Ettore, it must be admitted, had done something “downright inexcusable” to Segrè.

Just before joining Via Panisperna, Ettore was having a blast, enjoying perhaps his only happy days. With Luciano, Gastone Piqué, Segrè, and a new friend, Giovannni Gentile Jr., Ettore spent his days at Café Faraglino or the Casina delle Rose, discussing physics and philosophy, joking and gossiping—more often than not, just wasting time.

When the fashion of skiing and mountaineering hit Italy, Ettore’s group of friends sardonically set out to “conquer Mount Velino,” a peak some 2,500 meters (about 8,000 feet) tall, 100 kilometers (about 60 miles) away from Rome. Probably following a drunken bet, they set off without any preparation, renting boots and equipment on the way. Under the moonlight they started the climb from a nearby village, snow to their waists, getting lost almost immediately. When a storm unleashed its fury, they strategically repaired to a comfortable osteria, where a mountain expert informed them that it was only by a miracle that their stupidity hadn’t cost them their lives.

Throughout these early years, Ettore’s tricks continued to inspire awe. When Segrè, studying for an exam, couldn’t understand a mathematical proof, Ettore supplied him with a simpler alternative of his own. Serendipitiously, Segrè was asked precisely that proof during the oral exam, getting full marks from an awestruck professor. When Gastone felt bewildered by a four-page-long problem, Ettore commented, “Look, those four pages can be summed up in four words. . . .” Again, luck had Gastone impressing his examiners with Ettore’s elegant reworking of the problem.

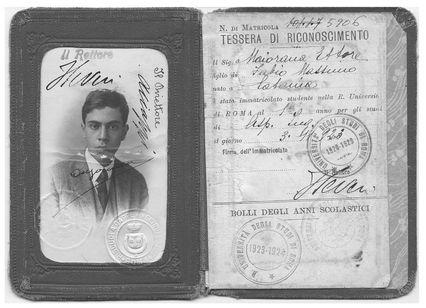

Ettore’s matriculation booklet from the University of Rome, where he was the ultimate nightmare to his teachers.

Ettore’s friends during this happy period describe him as a striking character. “His eyes were penetrating, dark, full of soul. He was one of those people that commanded attention just by looking at you.” Or “He was very singular. You wouldn’t find many people remotely like him.” Labels like “full of spirituality,” “very sensitive,” “skeptical of mankind,” and “downright pessimistic” abound.19 Ettore liked the philosopher Schopenhauer and was obsessed with Pirandello’s plays, in particular Six Characters in Search of an Author. Apart from science tomes, the only books found in his hotel room after he disappeared were Pirandello’s.

But even during this happy phase, Ettore remained aloof, his mind elsewhere. He regarded his teachers as idiots, insisting that they complicated things unnecessarily and didn’t know the subject matter in depth. At the end of one of his assignments he wrote, “The measurements have been executed and interpreted according to rules imposed by the competent authority. The foundation of these rules remains occult to us.” There are records of several rather acidic confrontations between him and his teachers. So Ettore studied on his own, in his room, valuing only discussions with his friends at the Faraglino or the Casina. He was happy, but he was also adrift.

Until Segrè beguiled him into joining Via Panisperna, at the young age of twenty-one. His scientific genius then flourished—for all his sins. For that’s when Ettore’s neurotic, traumatic streak resurfaced. It would stay with him until the assumed end of his days.

How does genius emerge? A formula has long been sought, when the point is that such a formula cannot exist. Genius is arcane, alchemical, almost accidental: It doesn’t lend itself to industrial production. But it’s clear that it’s triggered by personal relationships. As a teenager, Fermi and a friend had scoured the secondhand markets looking for science books, reading and discussing them avidly, even when they were the most inappropriate sources. The direct knowledge they acquired may ultimately have been useless—but the coloring, the resonance that this attached to their mental frame is unique, impossible to reproduce, nothing that can ever be matched by the battery force-feeding of schools.

The same personal rapport and camaraderie infused Via Panisperna, and its genius ultimately sprang from it. Regarding the discovery of the double helix by Watson and Crick, it’s been said that “there had to be an extraordinary interaction between . . . people before the mind could do what they did. Jim and Francis talked in half-sentences. They understood each other almost without words.” There was “[a] marvelous resonance between . . . minds—that high state in which one plus one does not equal two but more like ten.”20

Genius is the result of all this, but like a rare flower it’s also incredibly fragile. It attracts jealousy and must be protected. Italy is particularly fond of producing talent only to destroy it. That’s where Senator Corbino stepped in—he became the stone wall that protected talent from the prevailing harsh winds, like a Sicilian Giardino Arabo.

When Ettore arrived at Via Panisperna, the four first-generation, Mark I Boys formed a perfect team. Initially, Fermi was the theorist and Rasetti the experimentalist, but soon they were all doing whatever was needed, at great speed and with efficiency. They first worked in atomic physics but quickly ventured into the deeper waters of nuclear physics and field theory. As with Watson and Crick, the adjustments they made to one another’s personalities made for an easy and prolific collaboration. And as they churned out paper after paper, they became noted abroad.

There was a true all-out effervescence within the group. As Segrè put it, “The speed at which physicists were formed in Fermi’s school was quite amazing. Naturally this was due in part to the enormous enthusiasm [Fermi] imparted on young people, never preaching, but teaching by example. After a short time at Via Panisperna one found oneself completely absorbed in physics, and when I say completely I’m not exaggerating.”

Into this happy family Ettore stormed like a tornado. He was critical, he was better than they were. They feared him. His nickname, Il Grande Inquisitore, sums up the terror he must have inspired. His refusal to perform experiments—Ettore was a pure theorist—irritated everyone. And they were social—a well-oiled collective. He was not. He was an individual, a lone wolf. He was always an interloper among them.

Ettore’s mind during this period was in permanent turmoil. They’d tell him the results of their experiments, and he’d come up with an explanation almost instantly. He corrected the theories of Fermi, who didn’t fully understand the error of his ways until years later. Ettore became their in-house human computer. But more important than his circus-style tricks was his originality. He continually surprised them with new ideas and theories, explaining what the top minds abroad were struggling with: the neutron, the neutrino, nuclear forces, radioactivity. His talent looked supernatural, and he scared the shit out of them—especially Fermi.

To avoid myth making, one must recognize that a lot of Ettore’s apparent powers was mise-en-scène. One can trace the date of some of these “supernatural” flashes, in which new theories came to Ettore in one go, only to find that they were already neatly written down in his notes; that he’d actually solved the “new” problem just given to him a few days before. But the point is that the others didn’t know it: As with Feynman and other prodigies, Ettore was an equal mixture of genius and con man. And it takes a true genius to con the prank-loving likes of Fermi and Rasetti.

Segrè wrote in his book on Fermi, “Ettore was superior to his colleagues in intellect and depth. . . . His nature made him work on his own. He didn’t participate much in our studies because for him they were too elementary. But he helped us with theoretical problems and continually surprised us with his original ideas.” He was very tough in his appraisal of other scientists. “So much severity was nothing but a manifestation of an unsatisfied and tormented spirit,” according to Amaldi, but “such severity softened, even disappeared, close to friends; and was even worse with respect to his own work.”

One thing caused the group’s unmitigated exasperation: Ettore’s attitude toward publishing. The Boys published as much as they could, good or bad, ready or unready, following the “publish or perish” mantra that’s part and parcel of survival in academia. The rule at Via Panisperna was to publish the volume-fluffing crap in Italian, the good stuff in German. Ettore couldn’t have been more at odds with this. Presented with an experimental result, he’d immediately work out a theory, inscribing his calculations on a packet of his beloved Macedonia cigarettes, which he chain-smoked. Everyone would be impressed, but when they pressed him, saying, “Why don’t you write it up and publish it?” he’d reply, “What’s the point of publishing? It’s child’s play.” And he’d scandalize the Boys by smoking the last cigarette, crumpling the pack, and throwing it—along with the theory—into the garbage bin.

That’s how he never got credit for Heisenberg’s theory of nuclear forces and the neutron, the Weisskopf-Pauli second quantization of the complex scalar field, or the parity-violating properties of the neutrino, which earned Tsung Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang the Nobel Prize some thirty years later. They could all have been named after Majorana. But because he never published his work, only the Majorana neutrino—his inseparable soul mate—carries Ettore’s name today.

In the film I Ragazzi di Via Panisperna, Ettore works out that the atomic nucleus is made of protons and neutrons. Big deal? At the time, people thought the nucleus contained protons and electrons, in spite of the best evidence to the contrary, some of it discovered—but not understood—by Rasetti. Paradoxically, given his later career, even Fermi didn’t fully believe in neutrons as late as 1932—the proton and electron sufficed as the bricks of the world.

Yet for years, Ettore was aware that there had to be another particle in the nucleus, heavy like the proton but electrically neutral; there simply was no space for “nuclear” electrons. He also knew that a new force, stronger than electricity, must hold the nucleus together. He worked it out and then threw it away with the last cigarette as he crumpled the packet. This much is not apocryphal, as attested by the memoirs and TV interviews given by several Boys, many years later.

But in the film we see Ettore working it out at Fermi’s house, where he’d sought refuge from his mother, having been beaten up by the fiancé of the woman he was courting! That never happened, of course.

One night Ettore can’t sleep. And since he’s using a spare bed installed in Fermi’s studio, he goes through Fermi’s notebook (labeled “unsolved problems”) to pass the time. There he finds perfect evidence of the neutron’s existence. Except that the Boys “have understood nothing,” as he murmurs, with truth right in front of their noses.

In the morning, Ettore has it all worked out. But then he burns his work, page after page dissolving into ashes. When Fermi asks, “What was that?” Ettore replies, “Some old stuff I didn’t need,” adding, “My head is full of ghosts.” Fermi gives him the smile of a father figure—completely unaware of what has just happened. Months pass, and Ettore merely looks on as the Boys struggle with the problem of the stability of the nucleus, trying to fit electrons into a habitat where they can’t possibly live.

Even more apocryphally, the film shows an incident where one night much later Ettore catches a wannabe Boy breaking into the institute. Ettore teases the hopeful with an entrance exam: The subject is the nucleus. The intruder is keen and clever, but Ettore fails him because he says that the nucleus is made of protons and electrons. Ettore advises the terrified kid not to believe what he reads in books; and reveals to him the secret of the “neutral proton,” as he calls it.

The wannabe Boy is eventually taken on board—he’s meant to be Bruno Pontecorvo—and he’s shown as being present (an anachronism) when years later Fermi receives the news that Chadwick in England has discovered the neutron. Fermi is incensed: Why wasn’t the discovery made at Via Panisperna? The relevant data was all in his “unsolved problems” notebook! Pontecorvo’s eyebrows suddenly rise to the ceiling: Shell-shocked, he tells Fermi what happened on the night when he first met Ettore, and how Ettore had told him about the “neutral proton.” Fermi then understands what Ettore was turning into ashes at his house, all those years before.

A thermonuclear explosion takes place. Fermi seeks out Ettore and shouts at him: “Don’t you see what you’ve done?” Ettore is dismissive: “What’s the problem? Didn’t someone find it in the end?” “Yes, but it could have been you! Us!” Ettore becomes insulting: “I envy your love of physics, of the inanimate things. You love them because they’re dead.” Fermi slaps him and screams: “It’s not a matter of vanity! Can’t you see that to find something new and then burn it is criminal. It’s like a father burning his own child!”

I’m sure this never happened, or Ettore might have knifed Fermi in good Sicilian form. Because—as we know—there was a burnt baby in Ettore’s tragedy. He hadn’t burnt him, but someone in his family was accused of doing it. Yet Ettore did burn his neutron theory; that much belongs to documented reality.

In the film, this is why Fermi and Ettore fall out. They only make up years later, when Fermi is at odds with a bigger conundrum called uranium. Something unearthly had happened when the Boys bombarded uranium with neutrons—Fermi wasn’t quite sure what. Fermi journeys to Sicily to meet Ettore, where he lives in isolation at a remote farm. They talk and smoke the pipe of peace; Fermi leaves Ettore his notebook on uranium. It’s 1938.

On that night, Ettore can’t sleep, haunted by nightmares in which his mother parades him before visitors, forcing him to do mathematical tricks. He gets up and we see him going through Fermi’s notebook, feverishly doing calculations.

And then he raises his head from the papers and looks very seriously into a fixed point behind the camera.

Did he see it? We’re led to think so.

At dawn he burns his baby. Again. And a few days later, he vanishes without a trace.